Morality

Ethics

To bestow joy upon the least among us is to bestow joy upon the supreme goddess Óljamma herself. To inflict suffering upon the least among us is to inflict suffering upon her as well. For Óljamma possesses and shares all of consciousness, and she experiences all things.

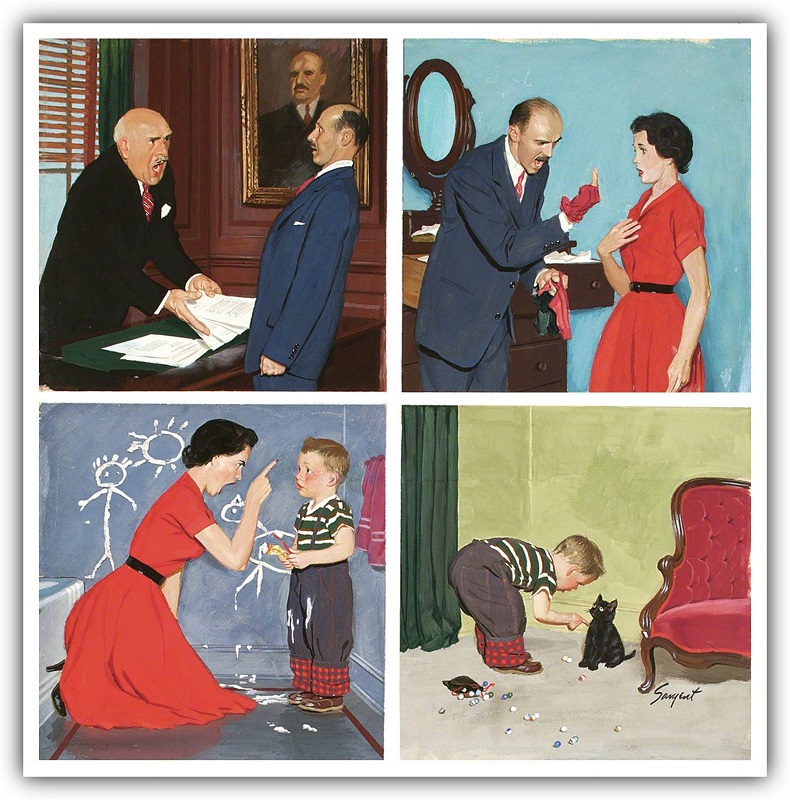

Within Perístanom, a proper normative ethics, of how people ought to behave, may be informed by pragmatic ethics, an ethical evolution characterized by Theodore Parker and Martin Luther King Jr. as the arc of the moral universe—long, but it bends toward justice. (This might also be the dominant comparative ethics of the world.) Through such ethics, humanity has been struggling, since the advent of civilization several thousand years ago, to advance and rediscover the moral wisdom of our earlier, persistent, natural state. Among soqjós, meta-ethics, an exploration of how ethical judgments can be adequately supported and defended, in turn may be described as democratic ethics (or popular ethics), wherein the morality of a particular course of action (or inaction) is ultimately determined and justified by the collective judgment of those affected by that action (or inaction). It may be noticed that the emphasis here is rather on behavior than on belief. No one should ever be judged for that which she, he, or zhe believes or does not believe, but instead for that which she, he, or zhe does or does not do. This democratic ethics is superficially relative and yet fundamentally universal. It acknowledges the potential legitimacy of local, artificial, positive law (if codified democratically), even as it recognizes the existence of innate natural law (crafted by biological evolution through natural selection). Within any human domain (whether ethics, language, culture in general, psychology, or even physiology or anatomy), trivial differences exist among humans who are nevertheless fundamentally the same in their humanity. Through normative ethics (prescriptive), comparative ethics (descriptive), and natural law, our common humanity allows Perístanom to adopt the fundamental moral principle of universality, commonly formulated as the Golden Rule.

The central imperative of every major spiritual tradition in the world is love—love not as a mere sentiment, but as divine action. Within the Christian tradition, the prophet Jesus sacrificed his life for disobediently preaching radical love:

“But I say to you who hear, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. To one who strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also, and from one who takes away your cloak do not withhold your tunic either. Give to everyone who begs from you, and from one who takes away your goods do not demand them back. And as you wish that others would do to you, do so to them.

“If you love those who love you, what benefit is that to you? For even sinners love those who love them. And if you do good to those who do good to you, what benefit is that to you? For even sinners do the same. And if you lend to those from whom you expect to receive, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, to get back the same amount. But love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return, and your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, for he is kind to the ungrateful and the evil. Be merciful, even as your Father is merciful....”

—Luke 6:27–36 (ESV)

The teachings of Jesus and those of other mystics reflect the profound realization that our apparent separateness is illusory, that I and the other are one. If the prophet seems here to advocate treating ourselves with less consideration than we treat others, perhaps he is allowing for selection bias. Or, as Linus Pauling once put it, “‘Do unto others twenty-five percent better than you expect them to do unto you.’... The twenty-five percent is for error.”

Perístanom follows in the anarchist tradition, as articulated by linguist Noam Chomsky:

“Well, anarchism is, in my view, basically a kind of tendency in human thought which shows up in different forms in different circumstances, and has some leading characteristics. Primarily it is a tendency that is suspicious and skeptical of domination, authority, and hierarchy. It seeks structures of hierarchy and domination in human life over the whole range, extending from, say, patriarchal families to, say, imperial systems, and it asks whether those systems are justified. It assumes that the burden of proof for anyone in a position of power and authority lies on them. Their authority is not self-justifying. They have to give a reason for it, a justification. And if they can’t justify that authority and power and control, which is the usual case, then the authority ought to be dismantled and replaced by something more free and just.”

Free Will

People typically experience a sense of being endowed with free will, that they encounter meaningful choices in their lives and then actively decide among their perceived options. In a way, this is similar to how early humans would have experienced the Earth as being stationary while the sun moved through the heavens from one horizon to another. The latter experience—of a geocentric universe—has been shown by modern scientific investigations to be inadequate for even a rudimentary understanding of celestial mechanics. Those willing to follow truth wherever is leads know that empirical findings need not always conform to our instincts or cherished beliefs.

We can explore the physical basis on which to judge the validity of a belief in free will. To begin, the best explanatory models in contemporary physics are general relativity and quantum mechanics (including the standard model of particle physics). The former is a classical theory which is deterministic—that is, it holds that reality is completely determined by precise physical laws. The latter theory, on the other hand, is characterized by irreducible uncertainty and randomness. Quantum mechanics itself and the ways of understanding its implications are subject to various interpretations. The two most prevalent of these are the Copenhagen interpretation and the many-worlds interpretation. The former is complicated with ghost particles and collapsing wave-functions, which would seem to necessitate unprecedented and mysterious kinds of physical processes. Meanwhile, the latter avoids those complications by positing an array of overlying universes, each slightly different from the next and for a time interacting at the quantum level as the universal wave function. This multitude of universes, this multiverse, includes and realizes within it every physically possible universe. This second interpretation would seem to be the more elegant of the two. That is, our most advanced theories in physics strongly suggest that any reality that could ever possibly exist, no matter how remote that possibility, actually does exist somewhere in the cosmos.

Thus, it would seem that determinism and stochasticism are the two fundamental principles governing the unfolding of reality. These principles are by no means contradictory. Instead, they are complementary, each principle prevailing at a different level of reality. If aleatory processes operate within any one universe, the multiverse as a whole is nevertheless entirely deterministic. This determinism implies two coherent and distinct attitudes toward reality: to deny the legitimacy of reality in its entirety (a pessimistic or demonic attitude), or to affirm the legitimacy of reality in its entirety (an optimistic or angelic attitude), even as we may work to influence its evolution. Peace may come to our lives when we appreciate that everything that happens, good and bad, here and elsewhere, is that which is meant to happen, is that which must happen somewhere. This means too that our individual presense in the cosmos is an inseperable part of that which has been deemed by our creator(s) as proper, as something that should be. Reality—with its delights and horrors, its local justices and injustices in turn—presents as a kind of sacred perfection, a terrible magnificence, with our typical judgments being provincial, if thoroughly understandable.

This arrangement leaves no room, for better or worse, for preserving free will. If, according to our best physical theories, every event in cosmic history is governed entirely by strict physical laws and random chance, applying as well to events involving human choice, then there is little physical basis for a belief in any meaningful free will—at least without the addition of a new, heretofore mysterious, and seemingly extraneous physical theory. This is not to say that free will absolutely does not exist, but merely that, in the face of contrary evidence, there is no rational basis for believing in its reality.

Beyond this purely physical critique of free will, biologists provide their own insights. Our behavior and personality, it seems, are governed by the complex interactions between our individual genotype and our formative experiences. This in itself does not preclude individual change, but it does suggest that even such change is itself more or less determined by our genes and our environment. We may assure ourselves that had we been subjected to the same formative stresses and provocations experienced by some criminal, we would have chosen differently, morally. However, even within a more conventional conception of choice, we cannot choose our genetic endowment and predispositions. Given the same nurture and the same nature within the same circumstances, we would all make precisely the same moral choices.

What are the implications of humans evidently having no truly free will? We may still speak of our making decisions, but those decisions, whatever they may be, are in a real sense predestined, at best manifested at a local level only randomly. Moral transgressions may still elicit guilt, shame, regret, and remorse from some, and anger from others, but we have the option of seeing also the deeper truth, that our “choices” and our behaviors are determined by our genetic disposition (nature) and our lived experience (nurture). Our choices are not separable from reality; they are apparent only. Moreover, at the most fundamental level, everything that we do is the inescapable result of blind physical laws and blind luck. Consequently, there need be no guilt about the past, no anxiety about the present, no fear about the future. Traditional religions have evoked this insight with various symbols such as Indra’s net, and God’s plan, but the fundamental idea is much the same. Judgment should be left to the gods; ours is but to love one another. Every major faith tradition in the world, from the Buddhist Pratītyasamutpāda to the Christian Sermon on the Mount, teaches oneness, compassion, and mercy toward all—including our enemies and ourselves.

We may yet choose to restrict the liberty of a criminal—if “choose” is the correct word—not properly out of revenge or punishment, but instead with humility and compassion and to protect the community. No punishment is required. Even where involuntarily sequestration of someone might somehow become necessary, for the safety of the rest of the community, the sequestered individual is still entitled to an equal voice within that community, or it is no longer a true democracy. In Jungian terms, a drive to punish wrongdoers often involves the projection of our own psychological shadow onto others, external to ourselves, where our own forbidden and frustrated impulses may be safely repudiated. Evidence suggests that many criminals have already been abused or neglected in their youth—in a sense, punished before ever committing their crimes. Even if not, how can we morally justify exacting revenge upon someone whose every action has been governed by immutable laws and indifferent misfortune?

This deeper perspective also validates the particular teaching—common to many religions—of trust in, and surrender to, the divine. Every possible universe, every possible situation wherein we might find ourselves, every possible action we might take, every possible thought we might think and emotion we might feel, are all absolutely and immediately real, are actually happening somewhere in the multiverse. Moreover, reality is governed by eternalism. It is integrated, interconnected, crystalline, and ultimately foreordained. If the spacetime of general relativity is to be regarded as an accurate description of reality, then acceptance of such a block multiverse becomes unavoidable, because of the relativity of simultaneity. Our inexorable motion through time is an illusion generated by our minds at every moment, a consequence of growing entropy and the second law of thermodynamics. Even our perception of spacetime as fundamental is an illusion, an artifact, a mental map constructed from an array of data both locally (within our minds) and globally (within the mind of Óljamma).

Our egos may wish to exercise complete control over our lives, may fight for such control, may even believe themselves to be at times and to degrees in control, although such local control, however appealing or unappealing the notion, is always an illusory conceit. In truth, the gods—wiser beings than we—maintain exquisite global control across all of existence. Many have found comfort, grace, and wisdom in that realization. How can we summon courage in the face of our suffering and apparent mortality, in the face of the unavoidable known and the impenetrable unknown? How can we forgive the transgressions and fallibilities of others and of ourselves? The key is to be found in our understanding that we are all playing our individual, impassioned, and ultimately deterministic/stochastic roles within an epic drama written by the gods. As Jaques observes in William Shakespeare’s As You Like It, “All the world’s a stage, / And all the men and women merely players...”.

Democracy

Óljamma, the sleeping goddess whose dream is the cosmos, is the source of all consciousness. We each experience in our lives typically only an infinitesimal portion of her eternal consciousness, as do all sentient beings everywhere within those universes wherein the gods evolve. Alone, our individual political opinions are to a greater or lesser extent biased by our limited perspectives, senses, and experiences. Together, however, we see further and more broadly, with an aggregate knowledge closer to the omniscience of the gods and of transcendent Óljamma herself. The surest path for us to better express the meaning and intentions of Óljamma in the world is to pool our individual experiences of consciousness into a community. This is the essence of democracy—those significantly affected by any particular decision should make that decision. This is also a safeguard for justice.

Some apologists for elite rule claim that democracy amounts to a “tyranny of the majority”. They may advocate limitations on majority rule to protect the minority, limitations that they seem to imply must be formulated by elites. This position presumes, however, that the majority would oppose limitations on government. Such limitations need have nothing to do with limiting majority rule and everything to do with limiting capricious rule, whether elite or common. Indeed, majority rule can be as deliberative as the majority wishes and requires no privileged interference.

Opponents of democracy may conjure images of mob rule (i.e., ochlocracy), as though a self-selected subgroup can ever properly be regarded as representative of a larger polity. Mob rule invariably means privileged sociopaths hurting the voiceless. (Its typical form is plutocracy.) Genuine democracy would in reality protect society from mob rule. Or opponents may cite historical examples of enslavement, war, and genocide popularly chosen by a privileged citizenry, as though the enslaved or annihilated people themselves had ever been consulted on matters affecting their lives and deaths. True democracy and crimes against humanity have never coexisted in history. Further, some may object that democracy fails to guarantee the best decision, a claim that begs the question: the best decision according to whom? And by whose criteria? Politics involves decisions based ultimately upon irreducibly subjective values. No more definitive method exists, even in principle, for determining the ‘best’ decision than democracy.

To be charitable, the assertion that the majority can potentially behave tyrannically may be true as far as that truth goes, but it willfully ignores a more fundamental truth—the only logical alternative to tyranny of the majority is tyranny of the minority, a worse tyranny by definition and far more dangerous in practice. Any decision (or indecision) affecting a group, however made, is political and will unavoidably involve curtailing some liberty. Imposition is inevitable in any nonunanimous decision. For example, the enforcement of a stop sign at a busy roadway intersection imposes a tyranny on the impatient of impeding free movement, but it also reduces a tyranny on the cautious of impeding safe movement. The question then becomes: Which tyranny is worse—imposing on any journey along a particular route additional impediments, or additional risks of injury or death? (Or stated alternatively: Which conflicting value do we ourselves deem more important in this instance—freedom of our movement or safety of our persons?) Any confrontation with mutually exclusive options—such as emplacing and consistently enforcing a stop sign, or not—asks of us that a choice be made among competing subjective values, a choice made either by us or, if we fail to choose, for us. A majority decision by those affected by the decision ensures the greatest amount of liberty and security for the greatest number of people.

Moreover, when power resides not with the majority but with the minority, however ostensibly enlightened, the temptation to exploit others is increased, because the benefits of exploitation are then concentrated and compounded to a powerful few, even as the costs are borne by an oppressed many. Through its dissipation of power instead, democracy utterly minimizes the lure and benefits of exploiting others and the opportunities to do so.

In order for a society to be considered meaningfully democratic, its economic life must firstly and necessarily be democratic. Economics is the study of nothing less than the system of production and distribution whereupon the very survival of the people depends. If tyranny obtains within a society’s economic institutions, which are fundamental and wherein its wealth is created, then tyranny inevitably obtains within that society at large. The presence of democracy within economic institutions is one definition, and perhaps the best definition, for the word ‘socialism’. Statism may be involved in socialism as well, but democracy certainly is, either directly or indirectly. Widespread economic hardship is almost always a function of economic inequality—of opportunity, of voice, of the shared benefits within society. The variable by which contemporary economists typically measure the level of a society’s economic equality is the Gini coefficient. All other economic variables—such as the rates of economic growth, of employment, and of inflation—are always of lesser importance.

Achieving economic justice means ensuring that the benefits provided to society by labor accrue to those actually performing the labor, to their dependents, and to their class. Practically, this means that profits generated through the economic activity of an enterprise must be shared among everyone working within the enterprise, perhaps proportional to each individual’s contribution of labor, but not of capital. (Capital, however obtained, may be properly regarded as representing past labor.) A society’s assets may be privately owned, and in the process of production even privately contributed, wherefor fair compensation for lost value may be provided. However, productive capital must never be leveraged to allow the renting (or owning) of human beings for the generation of profits. No profits should be extracted to external “investors”. Indeed, an investment class need not and should not exist. Moreover, enterprises must be managed democratically, with every worker in every enterprise enjoying an equal voice. An example would be the workers’ cooperative embedded within a market system: market socialism. Most, if perhaps not all, workers may reasonably be expected, out of feelings of solidarity with their fellows, to contribute, quite voluntarily, a portion of their wealth communally for the provision of the common good, to meet common needs, and to ensure the dignity and equality of all members of society. A humane, efficient, and stable socialist society would presumably make use of some combination of the relative advantages of decentralized markets and, particularly for meeting essential needs, of more deliberative economic planning under genuine democratic control. Democratized economic institutions also help ensure that state institutions do not become captured by any ruling class, who might use a coercive state to oppress the general citizenry. In our modern society, states and corporations are particularly powerful and de facto governing institutions, and their internal and external structures of organization must become democratic.

“A democracy is two wolves and a lamb voting on what to have for lunch.” —Gary Strand

No, a democracy is two normal people and a misanthropic sociopathic fabulist voting to share everything equitably.

The proper way for any group of individuals to make decisions concerning them all—be it family, community, society, or the entire world—is democratically, through free expression and free participation in a functioning democratic order. This means that consensus is built where practical, through deliberation both formal and informal, and, where impractical, the judgment of the majority of stakeholders determines the policy in question. Deliberation and execution of complex decisions may be delegated to democratically operated institutions and agencies. However, direct democracy is generally superior and is otherwise to obtain within the political sphere, the economic sphere, the corporate sphere, the ecclesiastical sphere, within any institution large or small, “public” or “private”, and within any other domain wherein decisions affecting the group can be made. Ultimately, the majority opinion is to be regarded as sacred, as the closest we mortals can reliably come to embodying divine intentions. VOX POPULI VOX DEI.

Solutions

Here are political proposals for a sustainable and just society in the United States and beyond:

1. Diversion of most military expenditures to immediate public investment in renewable energy.

2. Closure of all foreign military bases.

3. Universal basic income sufficient to meet all needs for decent survival (e.g., improved Social-Security-for-All).

4. Universal single-payer healthcare (e.g., improved Medicare-for-All).

5. Publicly funded higher education available to anyone.

6. Publicly funded elections at all levels.

7. Restoration of division between commercial banking and investment banking (i.e., Glass-Steagall).

8. Elimination of spurious rights to intellectual property (i.e., eliminating artificial scarcity).

9. Release of all non-violent offenders from federal and state penitentiaries, with savings used in treatment of substance abuse.

10. Income tax, capital gains tax, estate tax, and corporate tax on rich and their investments, to finance social programs.

11. Tariffs imposed on businesses opposing or avoiding these solutions or similar solutions in other countries.

13. Recognition of primary authority of Statute of International Court of Justice.

14. Creation of national high-speed-rail transportation, beginning along Atlantic and Pacific coasts and expanding nationally.

15. Workplace democracy mandated within all business enterprises, large and small.

16. Reorganization of all commercial enterprises as worker cooperatives, with outside funding (solely) from credit unions.

Doubters may claim the above proposals could never work, although we might expect a similar reaction were we to describe the contemporary United States to someone unfamiliar with its current economic order. Or they may claim insufficient money exists to finance such ambitious social programs. If so, they vastly underestimate the staggering levels of privately held wealth in American society. If all privately held household wealth and income in the United States were distributed equitably, every family of four would own $1,878,000 in assets, with $0 of debt, and an annual income after taxes of $253,000. (Figures are from 2025.) Instead, an arbitrarily privileged few, collectively wielding coercive power, are unfairly leveraging their wealth to effectively extort surplus labor and hoard ever more wealth, unearned, and which, for the purposes of actually improving lives, remains largely unused, uninvested, and stagnant.

Values

Ecclesiastes 3:1 (ESV) teaches us that “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven”, although the following assessment of moral values may hold as valid generally.

True Values: Adventure, Anarchy, Balance, Community, Compassion, Compromise, Conservation, Cooperation, Courage, Curiosity, Decentralization, Democracy, Diversity, Empiricism, Equality, Faith, Feminism, Forgiveness, Generocity, Gratitude, Heroism, Honesty, Hope, Humility, Humor, Inclusion, Integrity, Interdependence, Joy, Kindness, Life, Love, Mercy, Moderation, Mutuality, Openness, Optimism, Patience, Peace, Playfulness, Pluralism, Rationality, Responsibility, Sharing, Simplicity, Socialism, Solidarity, Sustainability, Transparency, Truth.

False Values: Absolutism, Arrogance, Autocracy, Capitalism, Certitude, Colonialism, Competition, Consumerism, Dehumanization, Dogmatism, Dominance, Duty, Elitism, Empire, Excellence, Exclusion, Greed, Hate, Hierarchy, Hoarding, Homophobia, Honor, Idolatry, Independence, Intolerance, Invulnerability, Jingoism, Leadership, Loyalty, Militarism, Misogyny, Nationalism, Obedience, Patriarchy, Patriotism, Perfection, Pessimism, Polarization, Pride, Propriety, Punishment, Purity, Racism, Revenge, Secrecy, Self-Reliance, Sexism, Superiority, War, Xenophobia.